Chicago, Part II: Frank Lloyd Wright, Oak Park, & Robie House

About a decade into my teaching career, I inherited the summer reading assignment for a junior-level honors American literature course I’d just been assigned. The novel? Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. I’m sure my enthusiasm and desire to read (let alone teach!) that beast of a book matched my students’, but one thing became clear: I was reminded of the little girl who, at a tender age, said she wanted to become an architect. I dug into resources that might inspire my students beyond the text and, in so doing, I found myself researching and reading about Frank Lloyd Wright’s work and legacy. I wanted students to “see” real-life examples of the kinds of works Roark’s character might have been imagining and designing, and my rabbit hole—I mean, research—led me to Fallingwater, the Pennsylvania home he designed in 1935.

Prior to researching Wright, I was only vaguely familiar with him and his work. I knew he had designed the Guggenheim in New York, which I had seen (but never visited) while in the city, and I knew one of my favorite bands (Simon and Garfunkel) sang a song about him, but that’s about it. But reading about Fallingwater led me to more research and then more, and then a bit more…truth be told, I’m a bit of a compulsive (obsessive) researcher when my mind settles on a particular topic of interest. At that point, I was in my early 30s, just beginning to navigate the tensions that would come to define my life for the next 15+ years: my insatiable curiosities and my innate restlessness. I was (and still am) looking for patterns, connections, and following the threads of curiosity to see where they might lead.

I’m so glad I started my tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work with the origin story itself: his home and studio, which Wright built in 1889 on a corner lot in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. The home, according to its website, was “the first over which Wright exerted complete artistic control.” In it, you can see the themes and motifs that he is widely known for: an abiding reverence for and congruence with nature, light, geometry, craftsmanship, and simplicity.

Prior to my visit to Chicago and to Wright’s home and studio, I had no idea he was profoundly influenced by Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-1800s—another moment of synchronicity for me. Those writers and their works deeply influenced my decision, while in high school, to become an English teacher. So to be in Wright’s home, to see the way he put those philosophies into his home and his studio—into his life—I was speechless. Another pattern. Another connection. Another thread.

After my tour of the home and studio, I continued over to the gift shop, where I picked up the device that would narrate the walking tour of other Wright-designed homes in the immediate vicinity. Armed with a map and the audio player, I was ready to meander about the neighborhood. As I viewed each home from a respectful distance and listened to the audio overview of each, I couldn’t help but wonder what it must be like to live in a home designed by one of the most brilliant architects of all time—and what it must be like to have tourists and architecture aficionados constantly walking by staring at your home! Ah, the blessing and the curse, I suppose.

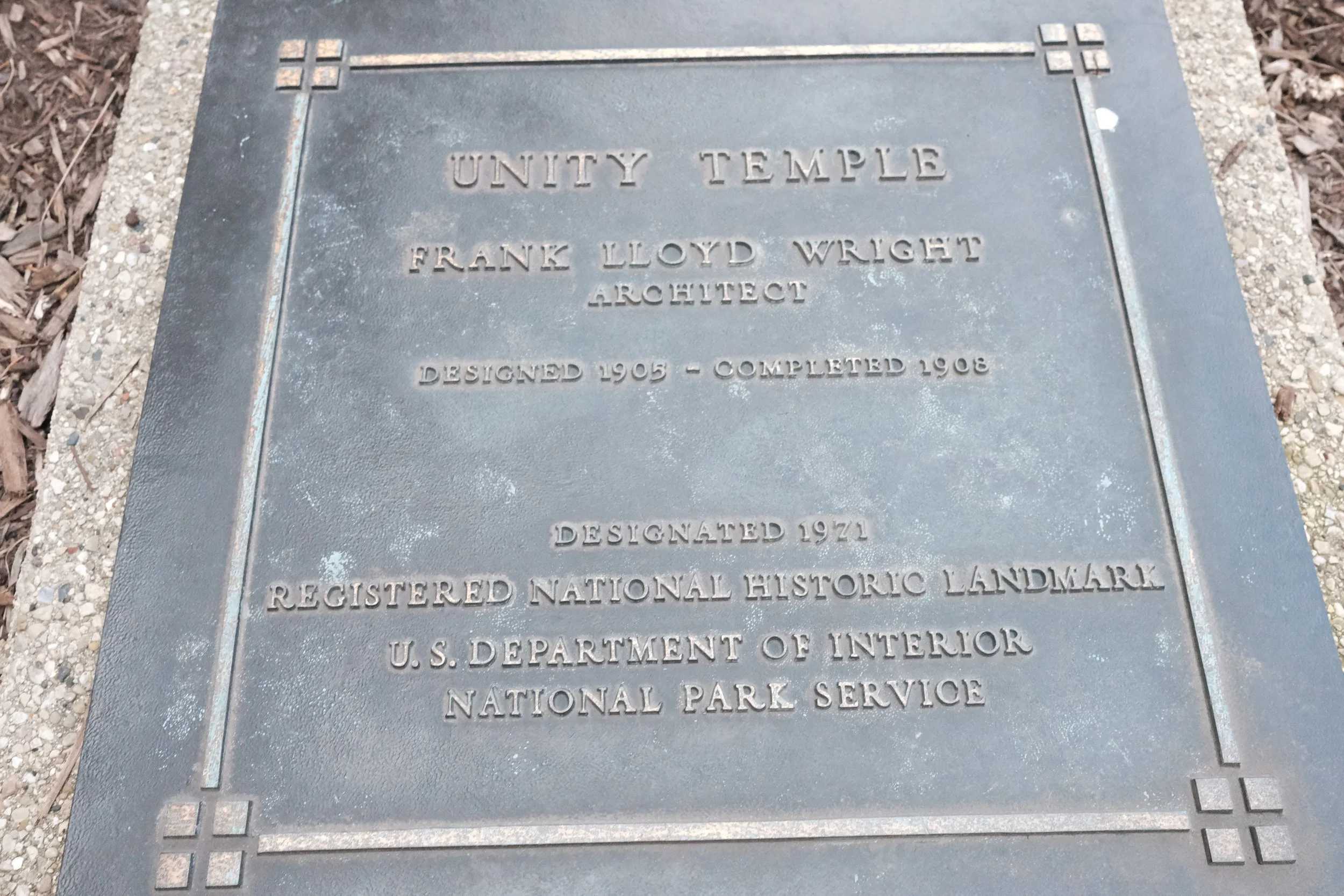

Before heading out of Oak Park, I had to be sure to visit the historic home—birthplace—of Ernest Hemingway. I’ve been a Hemingway fan since high school, when, I read A Farewell to Arms. That might have been the very first book to leave me speechless, and the fact that I read it on my own left me without anyone to talk to about it! Years later, when I included the book in my junior lit classes, I reveled in the conversations my students would have about Lt. Henry and Catherine and, of course, that brutal but oh-so-perfect ending. So many of Hemingway’s works have moved me over the years, and to think he grew up just minutes away from FLW’s Oak Park neighborhood! And then, one final stop to walk by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple, which was unfortunately closed to the public as it was a Sunday. Next time!

Fully inspired by all things Frank Lloyd Wright, I left Oak Park feeling like I had to see if I could get a ticket to tour the Frederick C. Robie House, widely considered one of Wright’s finest examples of his Prairie style. And I was! So the next morning, with just a few hours before my train, I took an Uber out to the campus of the University of Chicago (cue the When Harry Met Sally vibes!) and experienced my second Wright home. And wow, just wow. Here’s a brief description from the official webpage:

Completed in 1910, the house Wright designed for Frederick C. Robie is the consummate expression of his Prairie style. The house is conceived as an integral whole—site and structure, interior and exterior, furniture, ornament and architecture, each element is connected. Unrelentingly horizontal in its elevation and a dynamic configuration of sliding planes in its plan, the Robie House is the most innovative and forward thinking of all Wright’s Prairie houses.